The last decades of the XX century witnessed the erosion of the idea of veracity, originally attributed to the photographic image since the very early days. This was due, among other reasons, to the arrival and expansion of digital technology. However, in recent years, this same digital technology appears to be reverting that tendency. Ever since the emergence of social networks and the overwhelming democratization of image-making devices it seems that photography has gained back its ability to bear witness, to show and share with the world that 'I was there'.

However, not only services like Google or Facebook have turned around the status quo. In the current social context of Western Countries, is the combination of technology and the brand behind the images what has given back photography its almighty authority. In this line, You Haven't Seen Their Faces focuses its attention on other means of mass image production which is embroiled in a similar quandary: surveillance cameras. Months after the London Riots the ttrlMetropolitan Police handed out leaflets depicting youngsters that presumably took part in riots. Images of very low quality, almost amateur, were embedded with unquestioned authority due both to the device used for taking the photographs and to the institution distributing those images. But in reality, what do we actually know about these people? We have no context or explanation of the facts, but we almost inadvertently assume their guilt because they have been ‘caught on CCTV’.

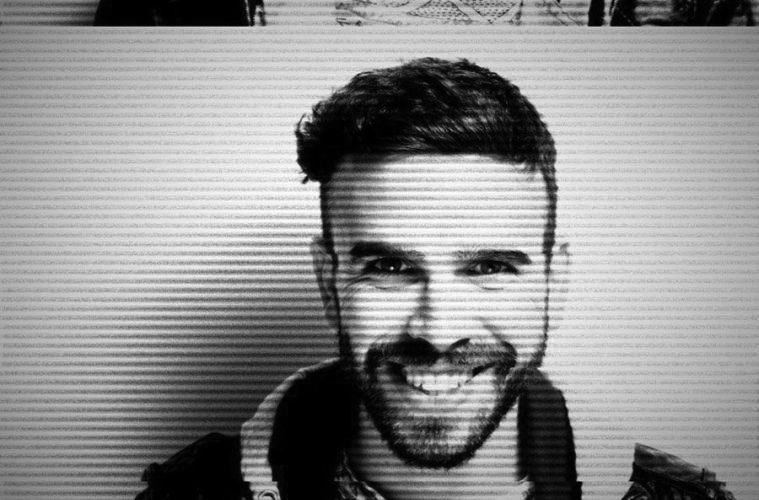

You Haven't Seen Their Faces intends to appropriate the characteristics of surveillance technology in order to create a very different set of images. The subject matter however is not the usual target of surveillance cameras, but a list of the 100 most powerful people of the City of London (according to the annual report by Square Mile magazine). The people here featured represent a sector which is arguably regarded in the collective perception as highly responsible for the current economic situation, but nevertheless still live in a comfortable anonymity. Hence the set of questions raised would be of the same sort: In the same way that we cannot possibly know if the youngsters portrayed by the police are actually criminals, we can not assume either that the individuals here featured are dishonest or have any involvement in the current banking scandals. The series focuses therefore on how a given image-production system such as surveillance cameras determines the way the spectators interpret the context surrounding the images. Do we take them in in the same way when presented in a leaflet as if encountered on a different medium? Does the fact that the police assumes the authorship of the images makes it different than when the author is an artist? How much does technology itself affect the reading of the image? Is it the inherent features of this type of technology that confers their truthfulness? What happens when those features are replicated precisely with other devious devices of digital manipulation?